Nowadays we can find beers labelled with 80 IBUs that can have less of a sensation of bitterness on the palate than another beer with 70 IBUs.

The compounds capable of adding bitterness may be tannins, proteins, yeasts and, mainly, the acids from the hops. If we assume that the bitterness contributed by the hops vastly outweighs that of all the other compounds, as in IPAs, and, although it’s true that the bitter sensation is offset by the beer’s density (which mainly depends on the alcohol and residual sugars we have), we can find beers with very similar densities and IBUs that have very different sensations of bitterness.

To clarify this a bit, we have to know what the EBU/IBU is, how it is measured and why, at times, it seems to be completely unrelated to bitterness.

Why is EBU/IBU used?

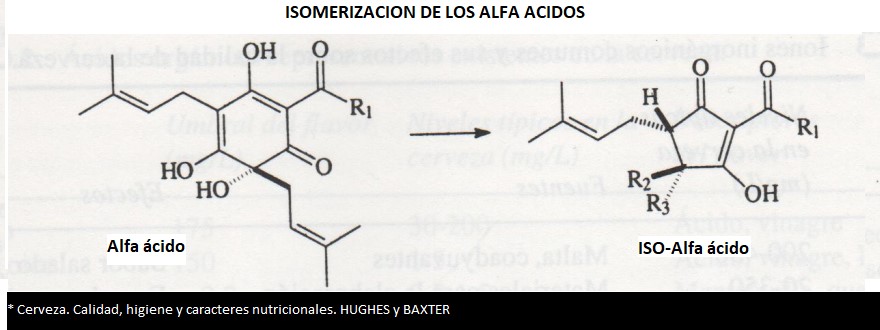

EBUs, European Bitterness Units, by definition are linked to the bitterness of the beer and, therefore, are one way of quantifying the bitter sensation of the beer. According to the definition of the European Brewery Convention, one EBU is equal to one milligram of ISO-alpha-acid per litre of beer, and these acids are one of the main sources of the sensation of bitterness in beer.

IBU (International Bitterness Unit) is a unit similar to the EBU that is defined by the American Society of Brewing Chemists using the units in the Anglo-Saxon system.

In practice, there is a great deal of confusion surrounding IBUs and EBUs, which in Spain are used interchangeably, possibly due to the American influence in the beer world.

You can find definitions of these concepts and others at Cervecistas or Birrapedia.

But if EBU/IBU is a bitterness measurement, how is it that we have beers with the same number of EBUs and a different sensation of bitterness? We need to look more closely at this subject.

How do we measure IBUs/EBUs?

By calculation

The measurement can be made theoretically, by calculation, if we know the number of kilos of hops added, the concentration of alpha acids that these hops contain, and the boiling time in the brew kettle for the transformation of alpha acids into ISO-alpha acids (IAA).

You can find out more about how EBUs are calculated theoretically at this link thebeertimes.

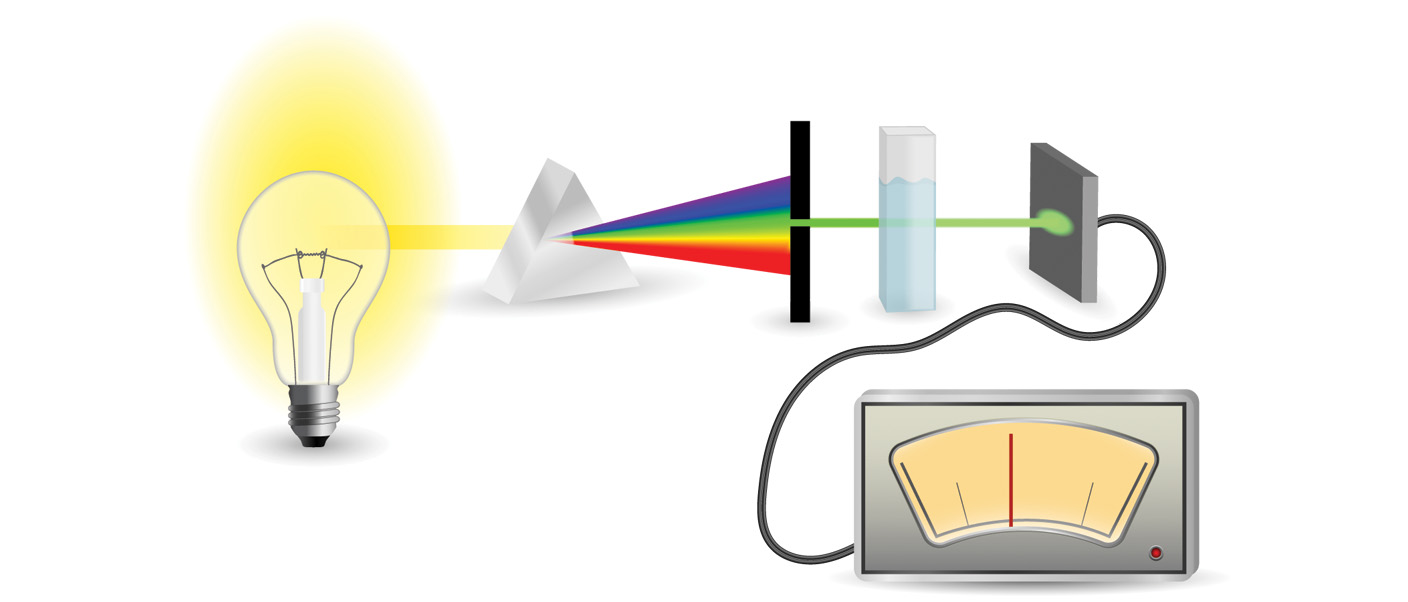

By molecular absorption spectrometry

Molecular absorption spectrometry is an analytical method that measures the amount of light that is absorbed (lost) when a ray of light passes through a sample, in our case of beer (IOB Method 9.1611)

This method enables us to determine the EBUs using a formula. This method is fast and the equipment relatively inexpensive, with semi-portable devices available at affordable prices.

By HPLC

HPLC-UV (high-performance liquid chromatography-ultraviolet) is an analytical method that combines separation of the different compounds in a sample (HPLC) with detection by molecular absorption (UV) in the ultraviolet range in the case of the bitter ones.

This device is quite a bit more expensive, although it also gives us much more reliability and precision than a spectrometer.

Differences between spectrometry and HPLC

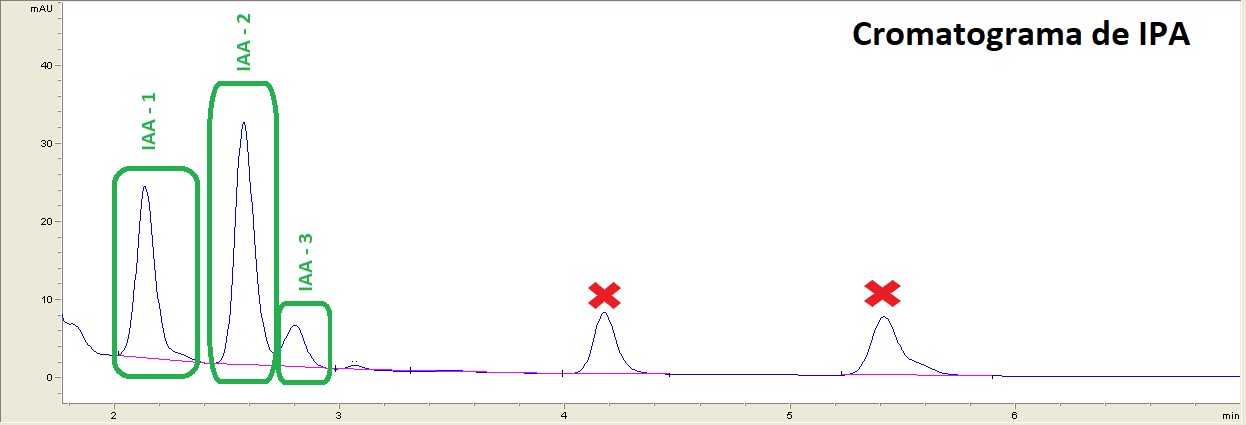

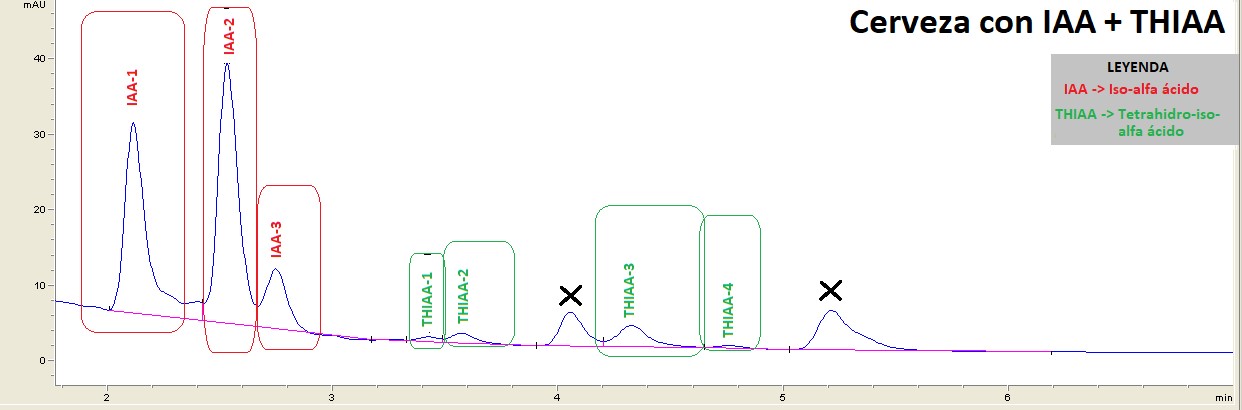

Although the measurement principle for both devices is the same, by measuring the absorption of a sample and relating it to the concentration, HPLC includes a pre-chromatography phase that makes all the difference, as it is capable of separating the different compounds in the sample and analysing the concentration of each compound individually, discarding the compounds that display absorption and do not interest us. Viewed on a graph, it would look like this:

In this image, we see the chromatogram of an IPA sample showing various peaks, each corresponding to a compound that displays absorbance, but not all the peaks belong to compounds that add bitterness. In this case, for example, only the peaks that are not marked with an X would be valid for quantifying bitterness, resulting in a bitterness of 21 mg/L or 21 EBUs. The peaks marked with an X correspond to different, non-IAA substances. This is known because the device was calibrated beforehand using reference standards.

This separation, which cannot be done by spectrometry, would give us an Absorbance signal that would be the sum of the 5 peaks, with the reading of 39 EBUs being quite a bit higher than the actual IAA reading.

Why is the analytical data between EBU spectrum and HPLC different in this case?

The reason in this case seems to be the addition of aromatic hops during dry hopping; these hops are varieties that are added to enrich the organoleptic profile of the beer, and they do not add bitterness. But some of the substances contributed by these hops do seem to increase the total absorbance of the sample.

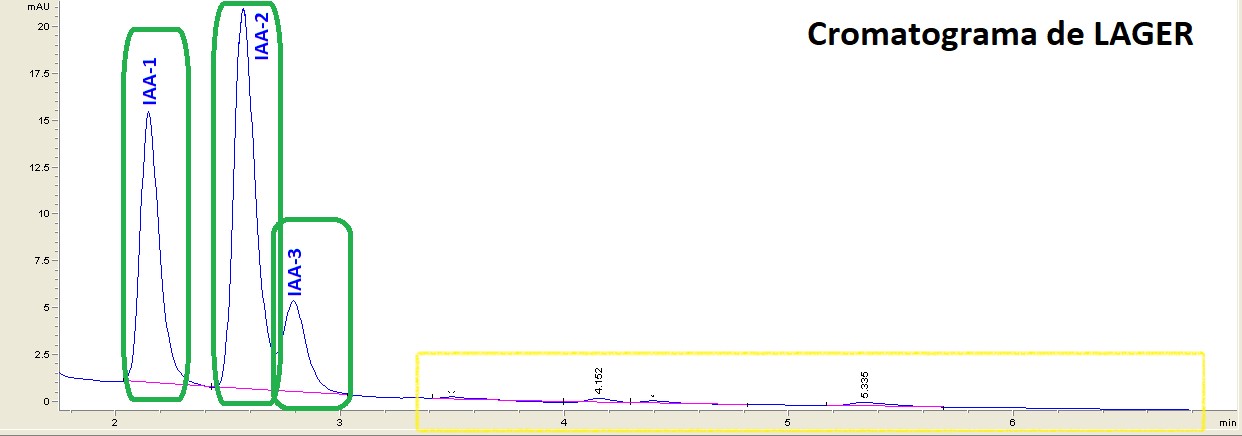

We can compare the chromatogram above with the one below, of a lager in which all the hops were added to contribute bitterness in the brew kettle.

We can see that no significant peaks appear from the 3-minute point to the end of the chromatogram, while in the chromatogram of the IPA we did find 2 major peaks.

So, in this case, the HPLC reading is 17.2 mg/L while the spectrometry one is 17.4 mg/L.

In addition to the compounds contributed by the hops, there can be different substances in a beer that absorb 270nm and interfere with the analysis, such as:

- Certain sugars

- Salicylic acid

- Ascorbic acid

- n-Heptyl 4-hydroxybenzoate

The big advantage of HPLC

HPLC can give us a great deal of information if we take the time to learn how to interpret it, as it can tell us the concentration we have of the different acids that make up the hops and whether we have modified acids, such as Tetras (Tetrahydro-iso-alpha acids) Rhos (dihydro-iso-alpha acids) or Hexas (hexahydro-iso-alpha acids).

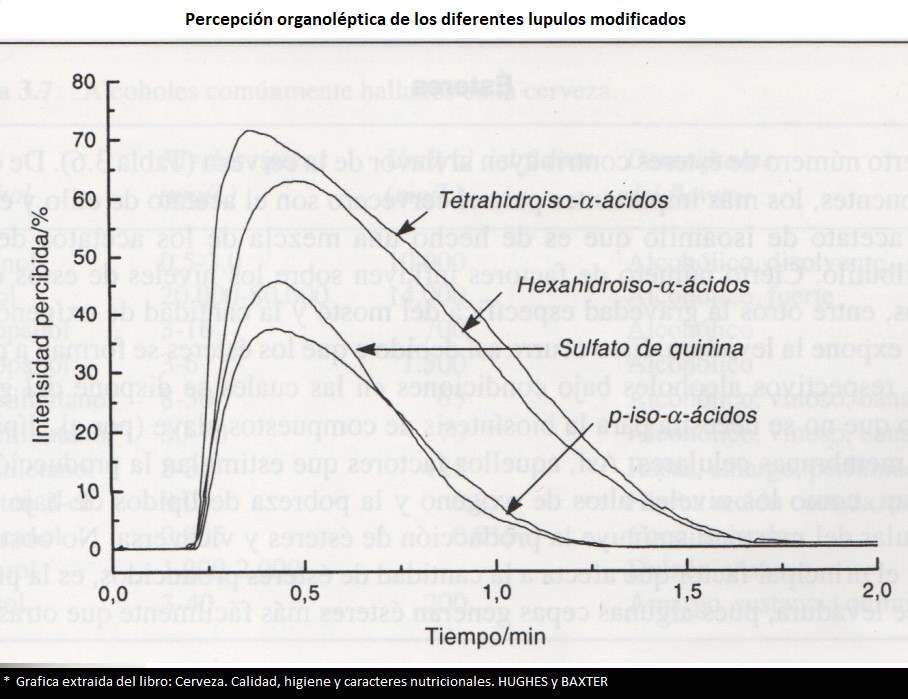

In the sensation of bitterness, modified hops play a very important role, as they have a bitterness sensation on the palate that is different from that of the IAAs. As can be seen in the graph:

HPLC also gives us a certain amount of qualitative information about the aromatic hops in our beer, or whether oxidation of the ISO-alpha acids exists, and therefore it is a powerful tool for brewers to adjust their process to the desired result.

Summary

In conclusion, as bitterness is linked to a sensory perception, it is much more difficult to compare its measurement to an analytical result; even so, there are instruments that can help us and serve as a guide in the process of brewing beers.

So, it’s best to try them and judge for yourself; you can make a tasting compass if it helps.

Among the methods of determining the bitterness units (IBU/EBU), HPLC is a much more reliable and robust technique than spectrometry, providing a more complete analytical result, particularly for beers with dry-hopping and other methods for aromatic hops.

If you would like to learn more about this subject, you can consult some of these websites: Cerveza Artesana, Beers and trips, Wikipedia

Literature consulted:

Kunze. Technology Brewing and Malting. Wolfgang KUNZE

A History of Beer and Brewing. Ian S. HORNSEY

Beer: Quality, Safety and Nutritional Aspects. HUGHES and BAXTER

Comments